In this essay, Luigi Rinaldi argues there is the possibility of using contracts in our organizing, if we use them to set a gold standard.

Introduction

Contracts between unions and employers have been a controversial subject in the IWW since its founding. They have been described by some as a needless compromise in the class war. Others have said they provide necessary breathing room for our struggles. While I used to hold a hard anti-contract position I have since moderated on the question. This was brought about by practical concerns. How do we, a revolutionary union, consolidate our gains and form lasting institutions in industries? How do we supersede the General Membership Branch as the primary form of organization in the IWW? How do we build Industrial Unions?

Contractualism exists, whether we like it or not. It is a political and practical reality and one that we must confront. Since they do exist and are the mainstay of the labor movement, and also have a fairly well proven record for longevity of labor organization, we should ask ourselves what we want to go into a contract. The IWW, despite its supposed hostility to the use of contracts, has realistically only had its success in shops with contracts. Whether this is the Philadelphia waterfront, the Cleveland machine shops, or more recently with its handful of shops in retail, social services, municipal services, and the railroads, these are the places where longstanding branches of the IWW have been able to retain a presence. Unfortunately for many reasons, namely lack of organizational focus, this has not turned into a general strategic focus on any particular industry.

Opposite this has been the semi-spontaneous growth of shop committees that come and go. This is perhaps best embodied by the history of the Starbucks Workers Union in General Distribution Workers IU No. 660. Starbucks was a valuable lesson for the IWW. It created numerous seasoned organizers. It even was able to make a handful of long-term gains in the company (though not the industry), notably holiday pay on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. But it also had a tendency towards spontaneity — workers and more importantly branches not taking the time to develop a comprehensive strategy for how they would take on a company like Starbucks. There are many stories of one or two person “committees” going public with the union and then being stamped down by the anti-union campaign. This is sometimes heralded as heroic minority unionism, but in reality it is a sign that the organization was naive and ill prepared to build a union. Shop committees came and went and the name of the SWU was kept for a long time, it had organization at numerous times and places, but rarely did it have a long term presence in these places. On the whole, the approach failed. Even if we can accept lessons were learned, important experiences gained, we still have to accept it as a failure.

Looking at Current IWW Contracts

I believe one problem relating to contracts and the IWW is that there has not been thought developed around what goes into a good contract, a Wobbly contract. Looking at much of the history of contractualism in the IWW in the past 30 or so years, we have mostly relied on adopting all of the AFL-CIO standards. We tend to have long grievance procedures, management rights clauses, and even no-strike clauses in our contracts. This is not the case for all of them, but for most.

The contracts from the Bay Area GMB are interesting. Most of them do not contain no-strike clauses, but do have a grievance procedure and management rights clause in place. We must squarely put these provisions in the negative. However, there are positives as well. The union is granted time to hold shop meetings. In the recycling yards, the company pays for ESL classes and even gives a bonus to those who complete the courses. Importantly, compared to another set of IWW contracts, the contracts require union membership.

Contracts from the Janus Youth Programs in Portland, Oregon actually allow provisions for an open shop in a state without right-to-work. In essence, the IWW has given away the requirement for workers covered by the contract to pay into the organization. There has been a Wobbly logic around the open shop. In some case, IWW members brag that right-to-work does not affect the IWW because members only voluntarily join the union. But if there is a contract in place, the union should enforce membership. Workers should not be able to get the gains of the union without being members of the union. Being members of the union is important for us as an organization, not just for the sake of numbers, but more importantly to we can more easily reach out to these people, to educate them about the IWW, and bring them in line with our principles. We are right to eschew dues check-off, but we should move towards ACH dues collection in order to maintain our membership in good standing. This would also likely keep membership up in shops like JYP, where the problem of lapsed membership tends to plague the organization (employees pay up when contract negotiations happen but then lapse).

What a Wobbly Contract Could Look Like

The Organizing Department Board of the IWW should have an idea of what a Wobbly contract should look like and be able to advise the locals on a technical level on how to negotiate. So what, then, should such an “ideal” contract look like?

I advocate what I consider to be a “minimalist approach” to contractualism. I believe the main thrust of a contract is to establish the union as the bargaining agent and to ensure union security. The idea of a minimalist contract is not new or even unique to the IWW. In fact, perhaps the best example is the first contract between the United Auto Workers and General Motors, which was all in all only a page long.[1]

Fundamentally, the minimalist approach is based on the power of the shop committee and the rights of union members. This means demands that put power in the hands of the union (and thus the workers), giving the organization the ability to talk freely with new hires, have paid time to do committee work, and company time to meet as a shop unit. Contracts that best exemplify this give the union time equal to new hire orientation done by the company. If new hires spend 2 hours with HR, they get 2 hours with a union delegate. Some contracts give delegates and officials paid time off to complete their duties (collecting dues, reports, grievance follow ups, etc) and UNITE HERE goes further — they allow for workers to take extended leaves to do union organizing elsewhere. Any good contract will require the employer to turn over the employee rolls to the union for outreach purposes. These are the types of provisions a Wobbly contract should pursue.

Wobbly contracts should reject the concepts of management rights clauses that have crept into contractualism in the AFL-CIO. We are a revolutionary union and we do not recognize the rights of management. There is no where in the NLRA that states management rights clauses must be signed, but getting rid of them will be an uphill battle, as the years of their use by the AFL-CIO have created the precedent that they are required for “bargaining in good faith.” As revolutionaries fighting for a new society we need to fight for control of the process of work in the here and now.

Connected with this is the other common provision in contracts: bureaucratic grievance procedures. The mainstream of contractualism has set up a system of “work now, grieve later.” This is really a way of sneaking management rights into the grievance procedure; the right for the company to keep making a profit trumps any grievance the workers might have. We ought to aim to define a range for acceptable grievance procedures, with “work now, grieve later” being off the table. The maximum we should accept is an outlined process, but that involves the shop committee from step 1. Our maximum goal should be a completely union-committee controlled grievance handling, or put another way, no defined grievance procedure.

It should, of course, go without saying that the IWW should not sign no-strike clauses or have a dues check-off. Having those as policy has actually helped us in negotiations where we were accused of “bargaining in bad faith.” This recently happened in the Mobile Rail campaign and the NLRB decision helped establish precedent that no-strike clauses are not necessary to have in a contract. Shifting this paradigm through taking hard positions on no-strike clauses, management rights, and bureaucratic procedures are important not just for our own union, but for the workers movement as a whole.

Finally, an important aspect of a Wobbly contract would be its duration. We should aim for short contracts, no more than 2 years in length. This will help us to better keep workers engaged in the union and their shop struggles. This would also be the strength of the minimalist approach: if a short contract is signed, one based around mainly enhancing and codifying the unions power, while much procedure is left up in the air, it means that direct action on the job is how the union wins its demands. It will take a strong committee based around direct action in the shop to win a contract like this, but I believe it is something worth fighting for.

Building a Strategy

Implementing this idea without integrating it into a strategy would prove as rudderless as the current course of the IWW. We should formulate a strategy based on several factors: where are we at, and where do we want to be?

Most members of the IWW tend to be in two clusters of industries — education (IU 620) and food and retail (IUs 460-640-660). The former tends to be heavily unionized already, the latter tends to have barely any unions. As an organization we need to have a conversation about how we got into these industries (I believe it was largely incidental). We have to have an analysis of the economic situation and know where we want to build ourselves up in the economy. Contracts become a part of that strategy by allowing us to build what I called “anchors” (other Fellow Workers I’ve talked to call them “footholds”). These are shops that serve as the foundation for future organizing on an industrial scale, rather than using the brand name approach many IWW unions have gone for (IE, Jimmy John’s Workers Union, Starbucks Workers Union, etc). A Fellow Worker put it this way: what if we organize a bargaining unit at Starbucks and workers from a different local chain approach the union about joining? The IWW is supposed to link these shops together in industrial organization. The brand name system separates workers by chain within an industry.

By building anchors in the industry we create a stable, industrial institution and grow that eventually into rechartering our Industrial Unions, making the numbers we’re assigned upon joining mean something materially. But we should not limit ourselves to where we have arrived at by accident. We should be deliberate in choosing targets. This means that we will need both local initiative, such as branch organizing committees, people willing to salt, as well as forces from the center — paid organizers who help workers form themselves into a local. It is long overdue that the union has staff that are able to systematically help workers organize and to train them to run the union themselves. I do understand the hesitation to talk about the issue of staff. There are financial constraints in the organization that prevent this from being immediately doable. That should not stop us from having this goal and organizing industrially to help make it a reality.

We can begin to organize industrially right now. When I first joined the IWW there were often steering committees of workers in industries putting their heads together to build the IWW on that basis. Then there was Food and Retail Workers United, an attempt to put together IU 460-640-660 organizing.[2] We need to understand why these attempts went away. I believe it was for a few reasons, in particular their limitations are simply being networks of people without a clear idea of how to form Industrial Unions. The other is the reliance of the General Membership Branch structure that tends to distract from organizing by attaching the IWW to numerous activist causes. We can and should begin to form industrial organizing steering committees as soon as possible.

Peter Olney, a retired organizer from the ILWU, talks about several important points of strategy in his analysis of the failed OUR Walmart campaign from the United Food and Commercial Workers. He says the UFCW did several things wrong. They were a union with a rather unimpressive track record when it came to organizing in the past 20 years, and yet they attempted to take on one of the most powerful companies in the world through a minority union approach. Onley notes that the UFCW should have “organized to scale” — in other words, picked targets appropriate for the resources they had available. This has been a problem in the IWW as well, taking on companies like Starbucks or Whole Foods. What Onley argues is that unions need to create anchors that build up their strength in an industry and scale up their targets as they grow. This should be part of an IWW strategy involving contractualism.[3]

Conclusions

Contracts are not the only way to have a union. They don’t make one union more legitimate than another. However, they can be an effective tool as part of an industrial organizing strategy to build organization. If we do organizing right, if we are patient, if we use the power of direct action on the job, if we build lasting institutions and use all the existing tools to do so, we can rebuild the Industrial Unions of the IWW. However, if we continue to act without an idea of where we’re going, without intent on how we get there, we are simply spinning our wheels. Our resources and time are unfortunately scarce. By adopting an organizing strategy that takes a principled approach to contracts, we can best put them to use.

[1] http://www.trimpesculpture.com/press/FirstUAW_GM_LaborAgreement1937.htm

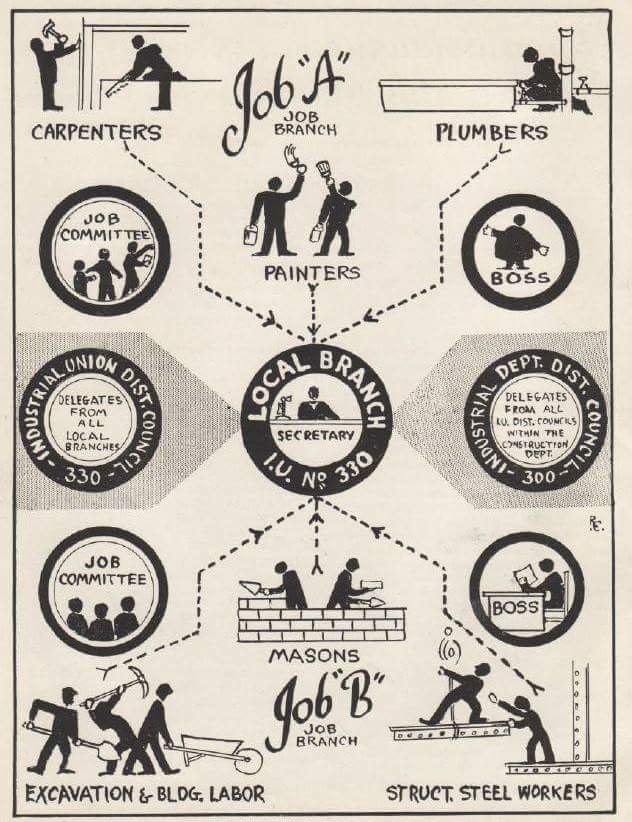

[2] There have been joint administrations before, but the FRWU tended not to function as one since it was built upon GMBs rather than a union of industrial branches. For an example see: http://www.workerseducation.org/crutch/constitution/210-310-330.html

[3] http://inthesetimes.com/working/entry/18692/our-walmart-union-ufcw-black-friday

Sometimes concessions are nice, and it can be worth it to secure a contract, especially in industries like food service where they are not the norm, or in industries like teaching, where new folks are expecting that to be the work of the union and aren’t open to other goals. However, I would advise against making it a tactical goal of the union in every case (which I don’t think you’re arguing for here, necessarily, but you never know who might just run with the idea).

At the end of the day, contracts don’t threaten to upend power relations between workers and bosses. They only crystallize those power relations at a certain point. Yes, maybe that point is more beneficial to the workers, and can result in good, concrete gains (pay, hours, safety). But the bosses will never negotiate themselves out of existence, and therefore the contracts cannot abolish the system that oppresses us. The vast majority of employers can play the long game better than the workers can, too, so if workers are satisfied with the contract, the employers will just slowly claw it all back.

A contract is only a step in workers’ education regarding the class struggle. You are right that they can be an effective tool, but they are defensive tools, and we must always be wary and keep offense on the mind as well! Thanks for opening this conversation.

LikeLiked by 1 person